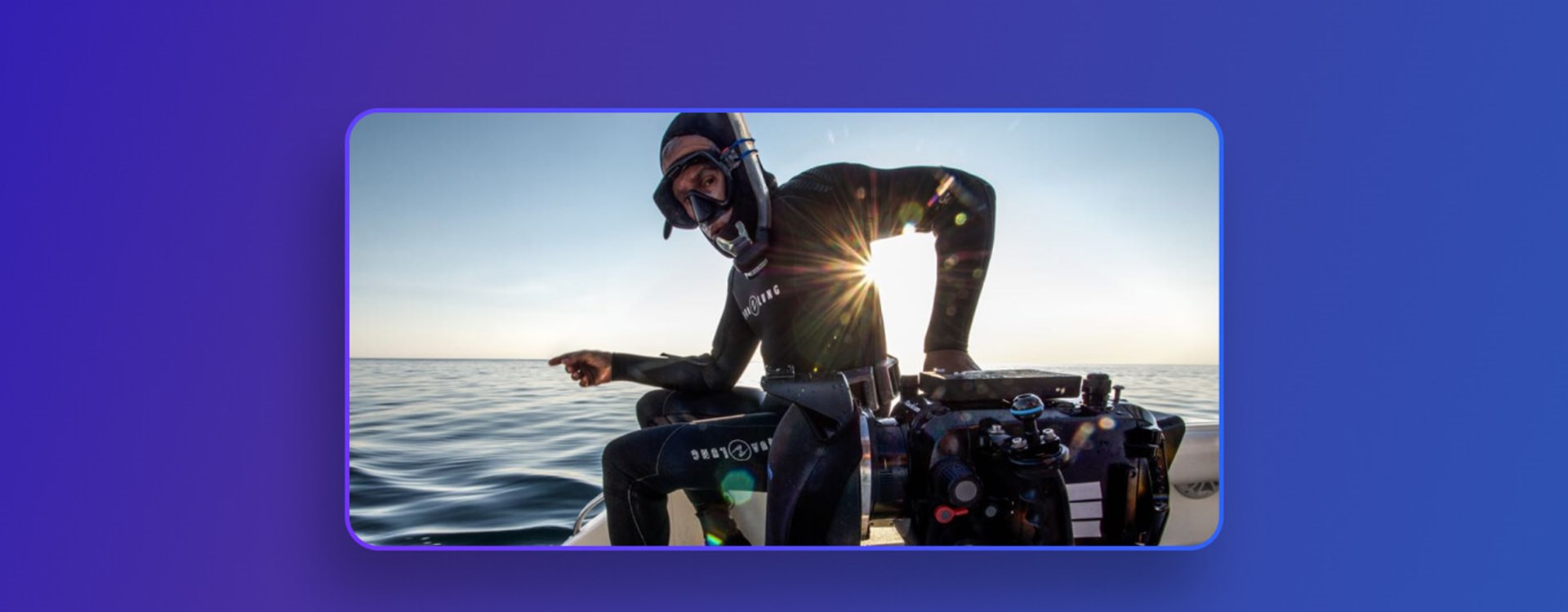

Alfredo Barroso is a BAFTA-Award-winning underwater cinematographer with over 30 years of experience, countless dives and hundreds of hours of beautiful footage under his weight belt. An expert on natural history and marine animal behavior, he's worked with the likes of the BBC, National Geographic, Discovery and many other renowned channels and producers on some of the biggest natural documentaries on TV.

We sat down to chat with him about his work – how he got to where he is today and how he captures such stunning underwater footage.

Artlist: If you could just sort of talk about your origin story. When did you figure out that this is what you wanted to do? Was there anything growing up that put you on this path?

Alfredo Barroso: Yeah. I was born in Cuba, so you can imagine it's very difficult even to become a diver. It's like an impossible dream. And then, I began by studying marine biology. Actually, I started when I was a kid.

When I discovered the sea, that was it. My soul was stolen by the sea, you know? So I just wanted to be in the ocean as much as possible. And then, the best option I could find was to be a marine biologist.

But then, 3 years into my studies, I said, "no, I don't want to be a biologist; I want to be a diver." I just wanted to be in the water all the time. I don't want to do science."

So I stopped out, and as soon as I could, I became a dive master, which was the other option you had in Cuba, which was very, very difficult. But really, what I always wanted was to make images, take pictures underwater…really, it was an impossible dream.

I tried photography, but it was impossible, and I realized I had to leave the country if I wanted to do this for a living. So as soon as I got out of Cuba, I got a video camera, and I realized I liked doing that more than taking pictures…

When I was a dive master here in Mexico, I began to gain experience with videography underwater. But it was a long time before I could become a professional cinematographer. It took quite a while.

A: So when was the first time that you took a camera underwater? What was the first camera that you were shooting with in the beginning?

AB: In Cuba back then, we were "colonized" by the Russians. So we had these Russian cameras, and I was trying to make houses for them but didn't have the material. I didn't have the know-how, so I could never take a picture with those things. So eventually, somehow, I got my hands on a Calypso, and that's the first thing I ever took underwater. It's a self-contained camera.

I could take pictures, but I didn't know anything about photography or lenses. As soon as I left Cuba, someone advised me to get some kind of little Sony video camera with a Gates housing. And so that's what I did.

And for years, I used different cameras with different Gates housing, and now I have REDs. But my very first video camera was one of those little Sony consumer cameras. I was so happy with that thing.

A: So, how did you end up turning it into a full-time job and a profession where it progressed to where you are today?

AB: I think the gods got tired of me wanting something (laughs). Because I didn't know what to do. I came from Cuba, and I didn't know anything.

After I left Cuba, I went to Quebec, and I only wanted to dive and travel, which I couldn't do in Cuba. But I didn't have contacts. I'm terrible at networking, for instance. I wanted to do all these things, and things started happening. Some people put me in touch with a person who worked on TV, and very soon after I got my first camera, I began selling footage to Quebec TV companies.

Then, I moved to Mexico and became a dive master. But I didn't like doing that; I just wanted to be a professional underwater cinematographer, but I didn't know how. And after a few years here, I started really getting sick and tired of being a divemaster; my camera was totally broken, and my underwater housing was literally falling into pieces…

And then a client that came to dive with me in Mexico got my footage and sold it in the US. So I started thinking that maybe I'm good enough to film after all, even if I didn't have any training.

Then my boss called me because someone was looking for footage or a cameraman. I didn't have the footage he wanted or a camera, but I did have a few videos on YouTube, which someone suggested I do.

At first, that person wasn't interested because I didn't have the footage he wanted. But then he went around Mexico looking for other people for that job, and several people sent him back to me. So eventually, he called me again and sent me to a meeting in Mexico City. That was for a telephone company.

In this big meeting, I showed my YouTube videos, and they wanted me for the job. And that was my very first professional job. And I said, "look, don't pay me any money; just pay me for the camera and the housing." So after that job, a French company contacted me, and I began to work with them. And from then on, it started rolling and rolling and rolling.

I worked a lot for NGOs on conservation stuff. And then National Geographic saw some of my videos on Vimeo and wanted to buy some of my footage. But I had already sold it to a British company, so National Geographic hired me.

Then another British company was looking for information about where I live here in Baja, and one of the guys who worked with me as a divemaster put them in contact with me.

And they were working with the BBC, and I've been working with these people for years. As a matter of fact, I just finished a fantastic 2-year contract filming for a series for them. So I wouldn't say it was a coincidence, but it was good luck – let's put it that way. Because I didn't know what to do, I was lost.

A: So it was a gradual process, right? You put out your footage and sell stock footage, then slowly, people got to know your name by word of mouth, and you just built on that? That's what started the ball rolling?

AB: Yeah. I have to say that YouTube helped me a lot. A friend in Canada advised me to put my videos on YouTube, and then it was just good luck that people looking for information called my old workplace, where I used to work as a divemaster, and they called me.

At first, this company just asked me for a lot of information about the animals, and they said, "well, you come with us, but you're going to be taking care of the car in the parking lot while we film." I wasn't pleased about that, but at least it was something, and in the end, I ended up filming because we had to film an event that didn't last very long. So they said, "well, you know how to film; here's a camera."

So they gave me a camera, I filmed, and it was good. And then they said, "Okay, next time you're coming with us to Costa Rica." It was just good luck and perseverance. You have to persevere. It wasn't easy for me to arrive where I am today.

A: So, what advice would you give to anyone looking to become a renowned underwater filmmaker, work on the big blue chip series and get to the level you're at today?

AB: First, don't listen to people with common sense! Don't pay attention to common sense. People will say, "No, no, you're never going to do it. How do you think you can compete against those guys?" Those kinds of questions. Common sense. Forget about it. Second, persevere. Don't give up. Never give up. Even when it seems impossible, you have to go for it. Your desire has to be bigger than your fear. And that's it. Perseverance; don't give up, and don't listen to common sense.

A: It's clear that it paid off for you to persevere and seize the opportunities that come up. Even though you were told you weren't going to film, in the end, they gave you the camera to film.

AB: Yeah. Another piece of advice would be to try to get in the industry in any way possible, even if it's like cleaning lenses or something. Because little by little, things can evolve.

Getting your foot in the industry is very hard. I know amazing cinematographers today that were called in by accident just to hold tubes on a shoot or something! And they progress from there. Because when you desire something, you just go for it like a locomotive with no brakes, you know.

You seem to play a lot with light and shadow. Do you think playing with light and shadows is essential for underwater footage?

It's like everything with filming – you work with lighting and shadows. Sometimes I use the sun a lot because I like how it looks. But I often just film what I can because animals are not actors. So I may have had time to compose some of the footage you see on Artgrid or in my showreel, but sometimes I didn't have time.

The animals come from whatever direction they want, and you do your best, but you always try to film in a way that gives depth to your footage.

A: What's your favorite underwater encounter?

AB: Oh, I have had so many. Actually, I recently had an encounter with Orcas, which might be my favorite. They were feeding on some fish. I was desperate to go down there because I could see them feeding with other animals, but they were pretty deep.

And then, finally, I managed to go down and be with them. That was quite amazing as an encounter. That was a dream. I want to do it again – to be close to Orcas while they feed right in front of me.

But I have had so many awesome encounters. Beautiful encounters with humpbacks and sperm whales. I like big animals. When you get that close, your brain doesn't process the information properly, and I love that.

A: You have both beautiful wide shots and also some fantastic sort of close-up angles as well. So how do you do that? You obviously can't change your lenses underwater. So how do you achieve the variety of shots?

AB: We use zoom lenses. Ideally, in the cinematic world you have primes and everything. But here and you have to be as versatile as you can to give the editor as many shots as you can – get as much variety of shots as you can.

Sometimes you have to react very quickly, because you might have something happening that only lasts 2 or 3 minutes. So if you have the presence of mind to do it, you get the wide-angle shot, the medium, and the close-up. And you move in and out to change camera angles and position, up or down.

It's fine if you have a very interesting shot happening because the thing by itself is just so awesome that you don't have to change anything. But at the same time, if you can give more variety, the guys can edit and make it more visually interesting. You have to think about that all the time. You have to think about the editor.

A: How is that for you when you get to see your footage in the final show, or you have someone like David Attenboroughdoing a voiceover over the footage that you shoot?

AB: Yeah, it's very beautiful. And sometimes editors don't even pick the best shots! I don't even know why. But yeah. It's always awesome to see your work like that.

A: What are you working on right now?

AB: We can't say much, but it is for a British series. We work a lot for the British at the moment. This August has been a dream of mine for a long time. This (the Orca) is an animal that I have kind of an obsession with, and finally, I have the time to do it here. They have been around for a while, but we've been traveling a lot for the last 2 years and never had the time to work with this animal here locally.

They're very close to where we live, and they are very difficult animals to film – difficult in the sense that you never know when they are coming. Sometimes they don't want to cooperate. When they want to cooperate, they are amazing, though.

This year we've been working for at least 2 or 3 series, now these jobs are finishing for all of those, so now we have to start looking for work, or waiting for them to come to us.

A: What does the future hold for you? Is there anything that you're hoping to do in the next few years, any sort of goals that you have in mind?

AB: I just want to keep doing this – I really like filming with big animals. I always want to be sent to film these big creatures. And then I have a passion project of mine that I wish to do, which I need to start developing. I already have the idea written down, and I have to start developing it. That's something that I want to do for myself that involves big animals.

I mean, that's a very hard question. For years I've been a tool and mostly at the beginning when I was starting to film, I said to local NGOs, you need to use me. Some people are good at sending messages, making messages, and making noise. I'm no good at that, but I'm good at filming. So I say here are my images. I still do it with people that ask me – a lot of people that ask me, I work for free for them, or give them footage. So I'm a tool for people that do conservation.

A: What do you think is our responsibility as filmmakers, particularly if you are shooting underwater, what do you feel your responsibility is? In terms of sharing the message about our oceans and ensuring that more people care and are aware of what's happening so that we can hopefully conserve and protect these ecosystems better?

AB: For me, it's very hard because I've seen changes happening here, the Hammerhead Sharks are gone. And when I was a kid in Cuba, we used to have Acropora Coral Gardens that were amazing…now those are gone. I've been crying on the water in Cuba, in places I used to visit that are not even a shadow of what they used to be.

It's very hard for me because I know what's happening and I'm seeing it. It's super difficult. I film, and then someone has to use those images to do something about it.

But in the end, there's not a lot people can do; they don't have the tools to impact the environment. Decision-makers, on the other hand, are the relevant audience. Unfortunately, most decision-makers are not good for the environment. They have no empathy; they don't understand this is important for the ecosystem; they only care about money. That's the sad reality.

So we actually filmed an informational video about the sharks here in Baja that showed how much money people made when there were sharks here, how there was a booming diving industry and how it declined because they hunted them. But there is hope because some places have been protected, and we hope the decision-makers will see it and realize how much money they can make if the sharks come back. So this was our contribution to conservation.

So if you are a good communicator, show the economic angle of conservation and aim for decision-makers.

A: Why did you upload your stock footage to Artgrid? How do you think filmmakers sharing stock footage can help their careers?

AB: I had stock footage on several agencies and hardly ever got anything. With Artgrid, they have been so good at promoting themselves. These guys have impetus and energy, and they are not asking me to upload the footage and do all the tagging myself! With some other sites, it was so tiring, and then I didn't actually get a lot of return, and they took a much bigger cut.

I wish I could send everything I don't own to Artgrid, but I can't even share it because I don't have the rights.

A: Where can people find you and learn a bit more?

AB: I have a website, which is very badly done because I decided to make it myself! Let's say I'm very good underwater, and I should stick to that! I should probably pay someone to do it for me (laughs)

You can find many of Alfredo's stock footage available at Artgrid.

To learn more and watch his showreels, head to https://www.azuloceano.com/

About Josh

Josh Edwards is an accomplished filmmaker, industry writing veteran, storyteller based in Indonesia (by way of the UK), and industry writer in the Blade Ronner Media Writing Collective. He's passionate about travel and documents adventures and stories through his films.